When we think of assembled objects, we are not likely to think of a concept of self. Instead we picture things like an IKEA bookcase or a model plane or a real-life car, objects that are put together from a finite and pre-determined set of pieces in a particular order and according to specific instructions. The bookcase frame precedes the inner shelf; lose a dowel and the object cannot be completed. There is usually only one way to put the object together and pieces are not usually interchangeable, so assemblers such as DIY enthusiasts, factory workers or robots have very little, if any room for creativity in their projects. Indeed, robots are ideally suited for the low-level tasks of executing the series of straightforward, single instructions that make up the process of assembly.

If the self is assembled on social media, it is not done by design from a pre-ordained, fixed collection of components. There is also no manual, much less an image of the finished product by which to check one’s work. It is do-it-yourself without a set of instructions.However, that is not to say that there is no goal that guides the selection and presentation of identity statements on social media, only that the hoped-for possible self that these statements serve to foster is known in outline alone.

This desired self is perceived obliquely, in broad lines of character that suggest such traits as affability, compassion, resourcefulness, or humor. The assembler may have only the vaguest sense of the entity she is piecing together. It may be the well-liked, triathlete lawyer or the bright, cultivated non-conformist, but a sense of a goal exists, however dimly perceived this persona is. I’m reminded of the iconic scene in Close Encounters of the Third Kind in which Richard Dreyfuss sculpts a mound out of mashed potatoes. It is the model of a place he has never seen and still does not know even exists, but the general shape of this squat peak has been implanted in his consciousness (you’ll also recall that his models get more accurate and significantly larger as the film progresses).

Given the considerable number and range of digital artifacts that the assembler could find, retrieve or create, it would be surprising if the small subset of pieces that she eventually brings together and puts on exhibit were selected randomly. But they are not. Of the 50 photos taken on a weekend kayaking trip, 5 will uploaded. Not all causes are supported, not all quotes shared.

The discrete items of social media content that find their way onto timelines, feeds and blogs,—the reposted Soundcloud set, say, or the photo from yoga class and this morning’s giraffe pancakes—clearly serve an immediate communicative purpose. They provide our friends and acquaintances with information on what we are doing. At the same time, however, these bits of content make evidentiary statements about a desired identity we wish to present. Indeed, the exhibition space of the Facebook timeline was explicitly designed to showcase such statements. It was also conceived as a posting board for similar statements generated by activity in other social apps, provided that the assembler has allowed to post on her or his behalf (“Noah Mason is cooking quinoa pilaf on Foodily.”, “Liz Angelou is reading Hilary Mantel in Goodreads”). In the words of Facebook itself, the timeline “lets you express who you are through all the things you do.” [emphasis added]

As these collected or crafted digitalia are brought together into one exhibition space—and here we can use the term assembled—they eventually yield a distinct and characteristic image. That they do so is partly a function of the curatorial activity of the assembler. No discernible image would emerge if the uploaded items were entirely random or too wide-ranging. Instead, we have the structured chaos that the legendary Ausstellngsmacher and curator Harald Szeeman claimed was the essence of a good exhibition. In this instance the structure is provided by the image of the desired self that is being presented. Items of content must fit in some way with this image, which, since Facebook in particular is a denominated rather than an anonymous medium, must in turn be broadly credible in the eyes of the friends and associates called upon to endorse this image. And the more focused the material, the better.

In assembling these digitalia the assembler is half engineer, half bricoleur (to borrow a distinction from Levi-Strauss). Like the engineer, the assembler can deploy a specific task-appropriate set of tools to create the artifacts needed for the project at hand: a photo of the first runner beans in the garden, a mixtape of edited in mashup software, an uploaded summary of a 10k run recorded on a heart monitor. Like the bricoleur, however, he will also have a (recently culled) store of materials at hand that can be used for a task unrelated to their original purpose, even when they still bear by the history of their previous use. A video of Andy Warhol’s ‘screen test’ of Bob Dylan or a fundraising call for an anti-bullying organization can be appropriated and inserted into a new context where they acquire a new meaning: evidence of coolness or social concern. Naturally this need not mean that the assembler is not interested in the early Dylan or does not actively support anti-bullying initiatives. It does mean, however, that these shared or re-located items function in some instances as borrowed insignia with symbolic power. As it is uploaded into the assembler’s personal online exhibition space, the object becomes imprinted with the likeness of its appropriator.

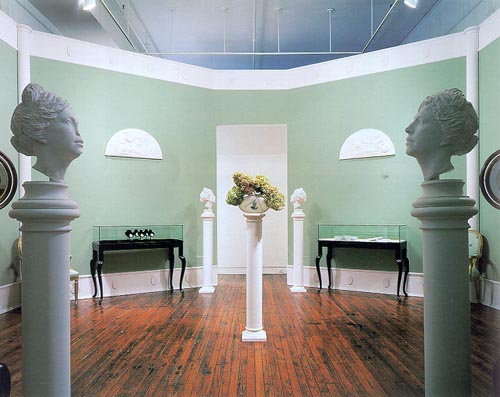

These borrowed insignia bring to mind the contents of Barbara Bloom’s installation ”The Reign of Narcissism.” In this work, Bloom fashioned a hexagonal space in the form of a salon, which she furnished with period furniture, plaster casts, cameos and vitrines with chocolates, books and porcelain cups. The upholstery, the face of the chocolate, the teacup—each object in the room bore the artist’s image or some other mark of her identity such as her signature or astrological chart. The installation is an acerbic comment on the fetishism of collecting and, in the perfect symmetry with which the furnishings and statuary in the room have been placed, on a pointless obsession with order. But it also serves as a striking visual metaphor of how the self is presented through the conspicuous display of collected objects.

Notes

I first encountered Barbara Bloom’s work in James Putman’s remarkable study Art and Artifact: The Museum as Medium, in which (among many other things) he discusses artists who have exhibited personal collections of objects as “museums”. (ed. Thames & Hudson)